Most

people today equate the 1950s with a “time of innocence.” That cliché seems to

oversimplify the period. I’m not sure how innocent it was living in a world

poised for nuclear destruction at almost any moment.

When it comes to the movies, Hollywood was in the fight of its life against its biggest competitor, television. So movies were dominated by new and bigger ways to tell a story, including wide-screen formats like Cinemascope and VistaVision, 3D, and other gimmicks.

Movies

featured a range of new female types, including such blonde dichotomies as Marilyn Monroe and Doris Day. New Method actors like Brando, Newman, and James Dean joined the ranks of

established male stars, such as Gable and Grant. There was the quick

rise of teen culture, with its rock ‘n roll, hot rods, and untamed youth.

Monster movies dominated the drive-in. Broadway musicals were adapted in big

productions. And westerns glorified the American West in full Technicolor.

If nostalgia illustrates a more naive cinema in the 1950s, it’s worth taking a look at a few titles from that decade that seem to exceed expectations. These are films that surprised me because they seemed to strongly comment on the era: Its morality, values, gender expectations; the idea that an old guard will soon give way to a younger, more explosive generation; and the underlying sense of doom and disappointment hovering over a post-war, nuclear age.

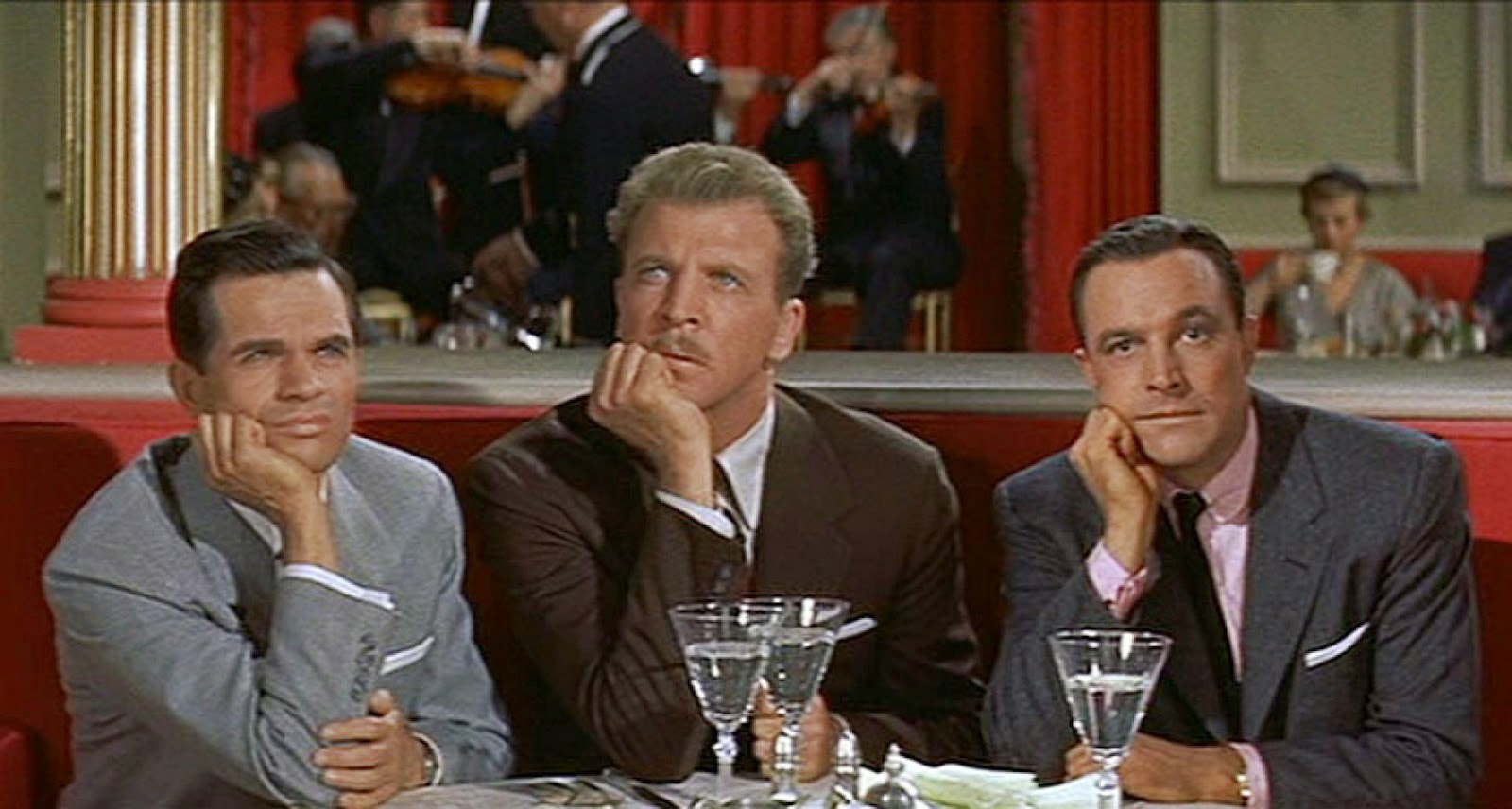

"It's Always Fair Weather" (1955): The Unhappy Musical

|

| They shouldn't have come. |

The plot involves three soldiers—Ted Riley (Gene Kelly), Doug Hallerton

(Dan Dailey) and Angie Valentine (Michael Kidd)—who served in the Army

together. When the war ends in 1945, they celebrate at a little dive bar in New

York City, vowing to remain friends forever and meet up again in exactly ten

years. Their joy in being home is demonstrated in a fantastic number that has

them tap-dancing with metal garbage can lids on their feet. (It’s amazing.)

Their loving departure is followed by a montage sequence that encapsulates

the ensuing decade. It reveals that none of their lives turned out quite as

they had hoped. Ted had dreams of becoming a lawyer, but now he’s a boxing

promoter with a gambling problem; Doug wanted to be a painter, but now works in

a thankless advertising job; Angie had wanted to become a chef, but now runs a hamburger

stand.

When the ten-year anniversary arrives, they grudgingly meet up. And it

turns out that not only do they have nothing in common anymore, they also don’t

even like each other. Since this is a big Hollywood musical, their contempt is

comically rendered in the song “I Shouldn’t Have Come.”

So how do we keep these guys together for the sake of the story? At the

restaurant where they’ve met, Doug sees his coworker Jackie Leighton (Cyd Charisse),

who gets the idea to have the men reunite on a popular TV show. Nothing says

sentimental like reuniting three war veterans in front of a national audience.

A guaranteed ratings grab!

That’s where the satire comes in. We meet the show’s host, Madeline

Bradville (Dolores Gray), who embodies everything unctuous about television in

the 1950s. Gray is iconic of the decade, born to wear her hair in the style of

the day and dressed to the nines in definitive fifties fashions. I can’t

envision her in any other decade. She is perfect to play the superficially

silken host of a typical fifties variety show, her over-powdered persona

fitting the role like a glove. But she’s in on the joke, which is what makes the

scenes in the TV studio work so well from a satirical perspective.

Cyd Charisse was an amazingly gorgeous dancer and capable comedienne. When

Jackie falls for Ted, she gets to do her showcase number set in a boxing gym (“Baby

You Knock Me Out”). It’s not to be missed.

Actually, there are no throwaway routines in “It’s Always Fair Weather.”

You get to see Gene Kelly dancing in roller skates (it’s genius), and Dan

Daily’s musings on being a cog in the wheel of the ad agency (“Situation-Wise”)

is a bitter comment on the work world of the 1950s.

When Ted refuses to fix a boxing match, gangsters are in hot pursuit, which

culminates in a melee on Madeline’s live show. This brings the guys back

together, albeit briefly, and helps re-set their lives to a certain degree. At the conclusion of the film, they part ways—more amicably this time—but it’s clear

they’ll never see each other again.

And that’s the

key to the movie: cynicism. At a time when musicals were typically bright and

sunny, “It’s Always Fair Weather” attempts to tell a story of disappointment

through song and dance. Even the title is a play on words. These guys were

really just fair-weather friends, at a point in their lives when they needed

each other. And is it really always fair weather? Nope, it’s not.

Although not a

commercial success at the time, the movie stands as an excellent example of the

Hollywood musical. And it shows that a film can be hugely entertaining and gently funny

and still be sharply satirical. The director, Stanley Donen, had a light touch, but a

bit of an edge too. Perhaps television was an easy target in 1955, but how many

mainstream, thought-provoking—yet light-hearted—satires on any aspect of American

culture have there been in recent years?

“Patterns” (1956): Big Business, '50s Style

|

| A movie poster for "Patterns." |

Fred Staples (Van Heflin) has recently joined Ramsey & Co., an industrial powerhouse headed by Walter Ramsey (Everett Sloane). Ramsey is grooming Fred to replace Bill Briggs (Ed Begley), an older executive in whom Ramsey has lost faith.

Bill is a good man who cares about his employees, but Ramsey is a ruthless executive whose primary care is making money at any cost. He repeatedly humiliates Bill in meetings and discounts his ideas. He takes every opportunity to publicly paint Bill as outmoded, out of step, incompetent, and unworthy of his current position.

Fred sees what Ramsey is doing to Bill; although Fred is ambitious and wants a greater position at the company, he encourages Bill to fight back. Ramsey, meanwhile, feels that Fred is a fool to care too deeply about the man he has been hired to replace.

After a final heated boardroom confrontation, Bill suffers a heart attack and dies. As a result, Fred realizes that he cannot in good conscience work for a man who cares nothing about his human capital. But before Fred can quit, Ramsey persuades him to stay on. Fred seizes the opportunity to sweeten the deal (a larger salary, stock options); but he lays out in no uncertain terms that he will work diligently to one day oust Ramsey. To this challenge, the venal Ramsey merely smiles.

This is a tough, intelligent little film. It takes place almost exclusively in either the boardroom or various offices at Ramsey & Co. There are a few scenes at Fred’s home and elsewhere, but the direction is very tight. This means that the dialogue is the key to the film’s power. It has a briskly intelligent script by Rod Serling (creator of “The Twilight Zone”), based on his teleplay, which was first broadcast in 1955. The film provides a historically important window on how business operated in the 1950s. In viewing it, though, one wonders how much has really changed, aside from clothing styles and office equipment.

The men—all excellent—are really the show here, which makes sense for a movie about big business in the 1950s. But fine and underrated actresses are also featured: Beatrice Straight is outstanding as Fred’s wife. Buffs should watch her in “Patterns” and then follow it up with her similar role, albeit 20 years later, in 1976’s “Network” as William Holden’s put-upon wife. (For that one, she won an Oscar.) Elizabeth Wilson, as Bill’s faithful former secretary who now reluctantly reports to Fred, is one of the best character actresses out there—and she’s still working at 93.

Since I always have to find a connection between one blog post and another, I must point out that a quick glimpse of the filmography of the late Lauren Bacall (the subject of my last post) shows that she has an uncredited role in “Patterns” as ‘Lobby lady near elevators.’ I’d love to know how she ended up in that bit part.

"Indiscreet" (1958): A Romantic Comedy for Grown-Ups

|

| Ingrid Bergman in her fabulous art-filled apartment. |

Anna Kalman (Ingrid Bergman) is a stage actress living in

London. Returning from a vacation in Spain, during which she met a man who didn’t

quite live up to her expectations, she laments to her sister Margaret (Phyllis

Calvert) that she will never fall in love. But just as suddenly, she meets Philip

Adams (Cary Grant), a charming financier who is a work acquaintance of her

brother-in-law Alfred (Cecil Parker).

Sparks fly between Anna and Philip, yet he makes it

clear that he is married. Even after they fall for each other, Philip insists

that, whatever happens between them, he cannot leave his wife. Their romance

continues despite his marital situation, and Anna finds herself falling deeper,

which creates conflict in her mind.

Then, Anna learns that Philip has been keeping something

from her. (I won’t say what it is.) On a night out with Philip, Margaret, and

Alfred, Anna regards Philip with muted contempt, knowing he has been lying. In

a climactic comic scene in her apartment, she tries to corner him, only to

discover his innocent reasons for not being entirely forthcoming.

I won’t tell you how it ends, but suffice to say that it

ends on a beautiful note. The joy of this film is the subtlety of Grant and

Bergman. They are both warm, witty, and urbane, and have excellent chemistry. (They

worked together only once before, 12 years earlier, in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Notorious,” quite a different type of movie.)

From its opening credits with a close-up of lush roses, to its

soaring music score, to the sets (especially Bergman’s art-filled London flat),

to its performers, I find “Indiscreet” refreshingly grown-up, not given to the coy conventions of most films about adult relationships of the 1950s. Watching the film’s

nimble direction by Donen underscores how incapable modern filmmakers seem to

be of making light comedies in which adults behave like adults.

While I thoroughly enjoy this classy production on its own

merits, I include it here because it seems to represent the ‘old guard’ I

mentioned in the post’s introduction. Here we have a 54-year-old Cary Grant and

a 43-year-old Ingrid Bergman playing two established people engaged in

a romance.

But their days as relevant movie stars were numbered, for as

we know in hindsight, the next decade represented the explosive younger generation, whose ideas about

sexuality and morality, manners and behavior would change considerably. Grant

and Bergman would soon represent the parents of that youthful generation. Ten

years later, this film would have been viewed as completely square.

"Bonjour Tristesse" (1958): Le Teenager Dangereuse

|

| One of several movie posters for "Bonjour Tristesse." |

“Bonjour Tristesse” opens in black and white, showing Raymond (David Niven) and his bored daughter Cécile (Seberg) lolling in a Paris nightclub, commenting on the passersby and basically idling their time. It then moves to their villa on the French Riviera, now in glorious color. (The location photography is stunning, by the way.)

Raymond is a careless playboy who spoils Cécile; they live an idyllic, decadent existence, and the daughter follows in the father’s footsteps, which he encourages. When Anne Larson (Deborah Kerr), an old friend of Raymond’s late wife, arrives at the villa, it sets off Cecile’s jealousies and fears that her carefree life will be disrupted.

Anne is an elegant, refined woman who, despite her affection for Raymond, is woefully out of her depth. He is a cad, and his affection for her is strictly superficial; he is unwilling to change from being the lothario he freely admits that he is. (In fact, he has a young mistress who basically lives with him at the villa.)

In her childish impulse to keep things as they were, Cecile aims to sabotage the relationship between Raymond and Anne. The older woman indulges Cecile’s immaturity up to a point, but circumstances lead her to flee the house in her car—which leads to a tragedy that changes Raymond and Cecile irrevocably, not necessarily for the better.

Otto Preminger’s output as a director was spotty, but I find “Bonjour Tristesse” to be an effective film that examines how similar the thought processes are for two immature, selfish people: One a middle-aged male; the other a young girl on the brink of womanhood. Raymond and Cecile are basically parasites who feed off and encourage the other’s self-indulgence.

The film closes in black and white again, this time fixing on Seberg in close-up as she considers what she has done. Her sorrow is palpable, yet the viewer wonders what, if anything, she has truly learned.

"The World, the Flesh, and the Devil" (1959): Not the End, but the Beginning

|

| One of the striking scenes of a bereft New York City. |

Ralph does, however, find newspapers that herald the end of the world. It appears that an unnamed nation has used lethal radioactive isotopes to kill off humanity.

Completely alone, Ralph makes it to New York City, but still finds no one. The early scenes are especially gripping, as you see this single man grappling with a city devoid of life. The photography is stunning, with outstanding visuals that underscore Ralph’s loneliness. You feel his despair as he walks along empty streets, abandoned cars at odd angles, newspapers rustling by his feet. Long shots of cavernous streets littered with debris indicate a civilized world that has come to a complete halt.

Taking

up residence in a swanky apartment, Ralph restores power so he has

light, and can even play records on a hi-fi. (It’s 1959, remember.) Becoming

increasingly lonely, he finds two mannequins from a clothing store and puts

them in his apartment so he has some company. But fake people are almost worse

than no people at all.

Ralph

eventually takes out his lonely frustration on the male mannequin, pushing it

off the apartment’s balcony. As it hits the ground, Ralph hears a woman’s

scream from the street below. There’s someone else alive in the city!

The woman is Sarah Crandall (Inger Stevens), who is white. Starved for companionship, the two live separately but spend every moment together. Sarah eventually falls in love with Ralph. But he is the product of a segregated society, and the conventions of his time force him to maintain a distance from her.

When the two discover a moving boat on the water, they find a very sick Benson Thacker (Mel Ferrer) at the wheel. Sarah and Ralph help Ben get well, but the dynamic has shifted; Ben falls for Sarah, and Ralph becomes his rival.

The situation degenerates and Ralph and Ben commit to fighting for the affection of Sarah. In a climactic standoff, shots are fired as they roam the empty city. But when Ralph comes upon the United Nations, he reads an inscription from the Book of Isaiah 2:4: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares. And their spears into pruning hooks. Nation shall not lift up sword against nation. Neither shall they learn war any more.”

Realizing the absurdity of this hunt to the death, Ralph confronts Ben and drops his gun. In turn, Ben cannot kill Ralph. They separate, but when Sarah appears, she takes each of their hands—one black, one white—in hers.

The movie isn’t a complete success, but it’s intelligently made and well-played by the three leads. It’s worth including in this post because it had something definite to say about two touchy subjects in 1959: Race relations and the threat of atomic annihilation.

In

these ways, “The World, The Flesh, and The Devil” is a pivotal film that was

ahead of its time. It raises important existential questions in an atomic

world, setting a tone that would be realized as the 1960s proceeded: The rise

of the civil rights movement, acceptance of interracial marriage, the anti-war

movement during the protracted Vietnam conflict, and the anti-nukes protests

that would gather momentum in the 1970s.

Conclusion

The 1950s has been called a

simpler, more naive time in America, and perhaps to a degree that is true.

Certainly by comparison to today, the morals, values, fashions, and standards

of behavior have changed quite a bit.